Preface

In the summer of 2022, a former colleague from my first job asked me if I wanted to help him teach a class at the University of Luxembourg. It was a class for the Master’s of Data Science, and the class was supposed to be taught by non-academics like us. The idea was to teach the students some “real-world” skills from the industry. It was a 40 hours class, and naturally we split them equally between us; my colleague focused on time series statistics but I really didn’t know what I should do. I knew I wanted to teach, I always liked teaching, but I am a public servant in the ministry of higher education and research in Luxembourg. I still code a lot, but I don’t do exciting machine learning anymore, or advanced econometrics like my colleague. Before (re)joining the public service I was a senior data scientist and then manager in one of the big four accounting firms. Before that, and this is where my colleague and I met, I was a research assistant in the research department of the national statistical institute of statistics in Luxembourg, and my colleague is still an applied researcher there.

What could I teach these students? What “skills from the industry” could I possibly share with them? I am an expert in nothing in particular. Actually, I don’t really know anything very deeply, but know at least a little about many different things. There are many self-help books out there that state that it’s better to know a lot about only a few, maybe even only one, topic, than know a lot about many topics. I tend to disagree with this; at least in my experience, knowing enough about many different topics always allowed me to communicate effectively with many different people, from researchers focusing on very specific topics that needed my help to assist them in their research, to clients from a wide range of industries that were sharing their problems with me in my consulting years. If I needed to deepen my knowledge on a particular topic before I could intervene, I had the necessary theoretical background to grab a few books and learn the material. Also, I was never afraid of asking questions.

This is reflected in my blogging. As I’m writing these lines (beginning of 2023), I have been blogging for about ten years. Most of my blog posts are me trying to lay out a problem I had at work and how I solved it. Sometimes I do some things for pleasure or curiosity, like the two posts on the video game nethack, or the ones on 19th century newspapers where I learned a lot about NLP. Because I was lucky enough to work with different people from many backgrounds, I always had to solve a very wide range of problems.

But that still didn’t really help me to find a topic to teach… but then it dawned on me. Even though in my career I had to help many different people with many different backgrounds and needs, there were two things that everyone always required: traceability and reliability.

Everyone wanted to know how I came to the conclusions that I came to, and most of them even wanted to be able to reproduce my steps as a form of double checking what I did (consultants are expensive, so you better make sure that they’re worth their hourly rate!). When I was a manager, I applied the same logic to my teammates. I wanted to be able to understand what they were doing, or at least know that if I needed to review their work deeply, the possibility was there.

So what I had to teach these students of data science was some best practices in software engineering. Most people working with data don’t get taught software engineering skills. Courses focus on probability theory, linear algebra, algorithms, and programming but not software engineering. That’s because software engineering skills get taught to software engineers. But while statisticians, data scientists, (or whatever we get called these days), are not software engineers, they do write a lot of code. And code that is quite important at that. And yet, most of us do work like pigs (no disrespect to pigs).

For example, how much of the code you write that produces very sensitive and important results, be it in science or in industry, is thoroughly tested? How much of the code you use relies on a single person showing up for work and using some secret knowledge that is undocumented? What if that person ends up under a bus? How much code do you run that no one dares touch anymore because that one person from before did end up under a bus?

How many people do you have to ping when you need to get an update to a quarterly report? How many people do you have to ping to know how Table 3 from that report from 2020 that was quickly put together during the Covid-19 lockdowns was computed? Are all the people involved even working in your company still?

When collaborating with teammates to write a report or scientific paper, do you consider potential risks? (If you’re wondering What risks? then you’re definitely not considering them.)

Are you able to tell anyone, exactly, how that number that gets used by the CEO in that one report was made? What if there’s an investigation, or some external audit? Would the auditors be able to run the code and understand what is going on with as little intervention as possible (ideally none) from you? But I don’t work in an industry that gets audited, you may think. Well, maybe not, or maybe one day your work will get audited anyways. Maybe it’ll get audited internally for whatever reason. Maybe there’s a new law that went into force that requires your work, or parts of your work, to be easily traceable.

And if you’re a scientist, your work does get audited, or at least it should be in theory. I don’t know any scientist (and I know more scientists than the average person, thanks to my background and current job) that is against the idea of open science, open data, reproducibility, and so on. Not one. But in practice, how many papers are truly reproducible? How many scientific results are auditable and traceable?

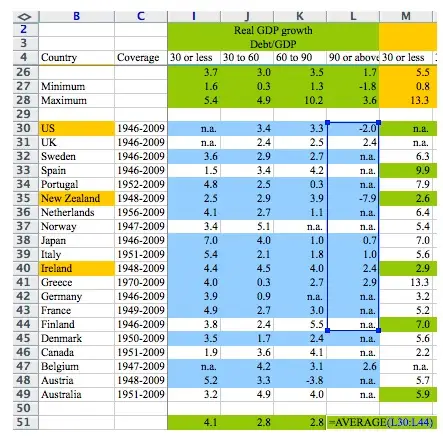

Lack of traceability and reproducibility can sometimes lead to serious consequences. If you’re in the social sciences, you likely know about the Reinhart and Rogoff paper. Reinhart and Rogoff are two American economists that published a paper in 2010 that showed that when countries are too much in debt (over 60% of GDP according to the authors) then annual growth decreases by two percent. These papers provided an empirical justification for austerity measures in the aftermath of the 2009 European debt crisis. But there was a serious problem with the Reinhart and Rogoff paper. It’s not that they somehow didn’t use the correct theoretical framework or modelling procedure in their paper. It’s not that their assumptions were disputable or too unrealistic. It’s that they performed their calculations inside an Excel spreadsheet and did not, and this is not a joke, they did not select every country’s real GDP growth to compute the average real GDP growth for high-debt countries:

(source to image, archived link1)

And this is not the only problem with this paper.

The problem is not that this mistake was made. Reinhart and Rogoff are only human and mistakes can happen. What’s problematic is that this was picked up and corrected too late. In an ideal world, Reinhart and Rogoff would not have used tools that make mistakes like this almost impossible to find once they’re made. Instead, they would have used tools that would have made such a thing not happen in the first place, or, as a second best, making it easier and faster for someone else to find this mistake. And this is not something that is only useful in research, but also in any industry. Being able to trust results, tracing back calculations and auditing are not only concerns of researchers.

So this is what I decided to teach the students: how they could structure their projects in such a way that they could spot problems like that during development, but also make it easy to reproduce and retrace who did what and when. I wrote my course notes into a freely available bookdown that I used for teaching. When I started compiling my notes, I discovered the concept Reproducible Analytical Pipelines as developed by the Office for National Statistics (henceforth ONS). I found the name “Reproducible Analytical Pipeline” (henceforth RAP) really perfect for what I was aiming at. The ONS team responsible for evangelising RAPs also published a free ebook in 2019 already. Another big source of inspiration is Software Carpentry to which I was exposed during my PhD years, around 2014-ish if memory serves. While working on a project with some German colleagues from the University of Bonn, the principal investigator made us work using these concepts to manage the project. I was really impressed by it, and these ideas and techniques stayed with me since then.

The bottom line is: the ideas I’m presenting here are nothing new. It’s just that I took some time to compile them and make them accessible and interesting (at least I hope so) for users of the R programming language.

At least my students found the course interesting. But not just students. I tweeted about this course and shared the notes with a wider audience, and this is when I got very positive feedback from people that were not my students. People wanted to buy this as a book and go deeper into the topics laid out. This is when I realised that, as far as I know, there is not a practical book available discussing these topics. So I decided to write one, but I took my time getting started. What finally, really, got me working on it was when Dmytro Perepolkin reached out to me and suggested I contact several persons to get their inputs and ideas and get started. I followed his advice, and this led to very fruitful discussions with Sébastien Rochette, Miles McBain and Dmytro. Their ideas and inputs definitely improved the quality of this book, so many thanks to them. Also thanks to David Solito, Matan Hakim, Stas Kolenikov, Sam Parmar, Chuck, Matouš Eibich, Jonathan Moore, Alain Vagner and Matthias Meiksner for proofreading the book and providing valuable feedback and fixes. And thank you, dear reader, for picking this up!

This book is divided into two parts. The first part teaches you what I believe is essential knowledge you should possess in order to write truly reproducible pipelines. This essential knowledge is constituted of:

- Version control with Git and how to manage projects with Github;

- Functional programming;

- Literate programming.

The main idea from part 1 is “don’t repeat yourself”. Git and Github will help us avoid losing code, and losing track of who should do what in a project (even if you’re working alone on a project, you will see that using Git and Github will save you many hours and headaches). Getting familiar with functional and literate programming should improve the quality of our code by avoiding two common sources of mistakes: computing results that rely on the state of our program (and later, the state of the whole hardware we are using) and copy and paste mistakes.

The second part of the book will then build upon this knowledge to introduce several tools that will help us go beyond the benefits of version control and functional and literate programming:

- Dependency management with

{renv}; - Package development with

{fusen}; - Unit and assertive testing;

- Build automation with

{targets}; - Reproducible environments with Docker;

- Continuous integration and delivery.

While this is not a book for beginners (you really should be familiar with R before reading this), I will not assume that you have any knowledge of the tools presented in part 2. In fact, even if you’re already familiar with Git, Github, functional programming and literate programming, I think that you will still learn something useful from reading part 1. But be warned, this book will require you to take the time to read it, and then type on your computer. Type a lot.

I hope that you will enjoy reading this book and applying the ideas in your day-to-day, ideas which hopefully should improve the reliability, traceability and reproducibility of your code. You can read this book for free on https://raps-with-r.dev/, or if you want you can buy a DRM-free PDF or Epub over at https://leanpub.com/raps-with-r.

You can also buy a physical copy of the book on Amazon.

If you want to get to know me better, read my bio2.

If you have feedback, drop me an email at bruno [at] brodrigues [dot] co.

Enjoy!