16 Conclusion of part 2

Congratulations, we are done going down the reproducibility iceberg. Our project should now be entirely reproducible. I showed you how to reuse the same R version and the same package library as the one that was used to develop the pipeline originally. If in addition you’ve used the software engineering best practices from part 1, your project is also well tested and documented.

This part of the book focused on the operating system your pipeline runs on. It’s a bit trickier to “freeze” an operating system, like we froze the R version and the packages library. Strictly speaking, we should develop and deploy our pipeline on the same operating system. If you’re using Ubuntu as your daily driver, that is not an issue, but if you’re a Windows or a macOS user, then this could potentially be a problem. After all, Docker images are based on Ubuntu (or other Linux distributions), so the best we can do is either start developing with the end in mind from the beginning; which means that we develop our project from inside a Docker environment, or we must ensure that running the pipeline inside Docker returns the same results as on your operating system of choice. This should most of the time not be an issue, but as already mentioned in this book, running the same code on Linux or Windows does sometimes return different results (this is rarer, at least in my experience, when comparing Linux to macOS).

But there is yet another, potential, issue. Let’s assume the best case scenario: the pipeline returns the same result inside Docker as on your development machine (which should be the case most of the time anyways). Is using Docker truly the best we can do? Is the pipeline truly reproducible? Well, strictly speaking, not quite. Indeed, the base operating system inside Docker also gets updated. So if you build an image based on Ubuntu 22.04 today, and then again in 6 months, the operating system is not the same anymore, because the software it ships got updated. So even if the R package library and R version remain fixed, the operating system does not. Now, I realize that this is really pushing it, but I want to be as thorough as possible. So there are two ways around this, if you really, absolutely, need also Ubuntu to remain frozen.

The first solution is the simplest and is explained in the reproducibility page1 of the Rocker project. The idea is to use a digest, which is the equivalent of a commit hash on Github but for Docker images instead. As the example in the linked page above shows, instead of this:

FROM rocker/r-ver:4.2.0which would base your Docker image on the latest Ubuntu 22.04 shipping R version 4.2.0, you would use this:

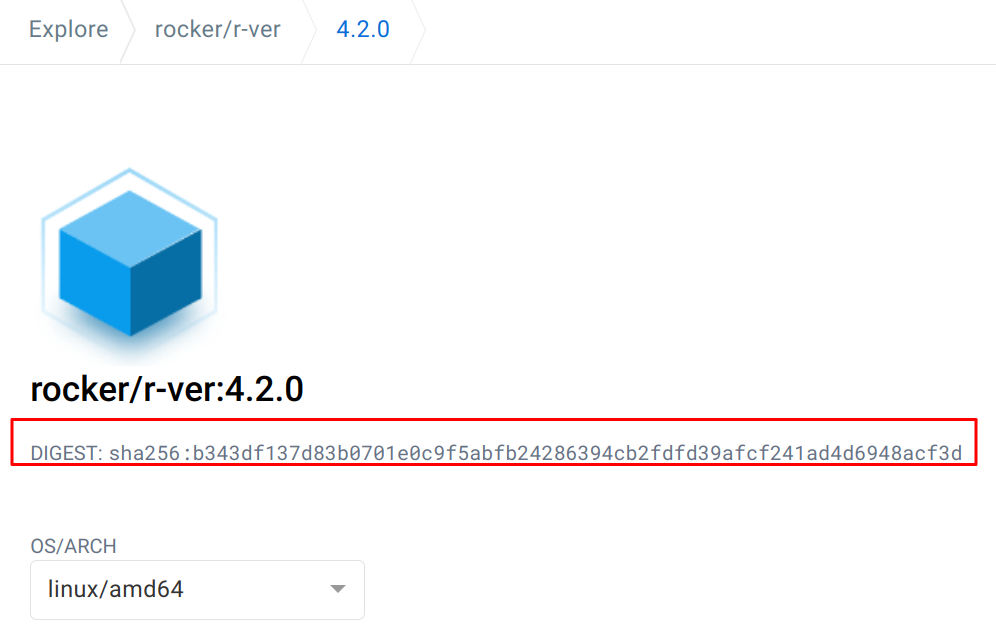

FROM rocker/r-ver@sha256:b343df137d83b0701e0...which is the digest of the latest rebuild of that image. You can find digests on the Docker Hub page:

If you use a digest instead of a tag, it doesn’t matter when the image gets built, you’ll be using the exact same Ubuntu version under the hood that was current at that time.

The second way around this is to use a functional package manager like Guix or Nix. As I stated in the reproducibility iceberg, this is outside the scope of this book, but the idea of these package managers is that they allow users to reproduce the entirety of a project (so including the operating system libraries) to the exact same byte. If you want to know more, take a look at Vallet, Michonneau, and Tournier (2022) (open access article2) which shows how Guix works by reproducing the results from another paper.